In Depth: China Makes Further Inroads in Popularizing the Yuan

By Wang Shiyu, Zhang Yuzhe, Wang Liwei and Zhang Ziyu

The yuan made deeper inroads as a global currency in the first quarter this year, as countries including Russia and Brazil have joined China’s drive to boost the currency’s use in cross-border settlements amid headwinds including a global dollar shortage and the prolonged war in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, China has been ramping up efforts to build up the financial infrastructure designed to cater to cross-border yuan settlements, such as setting up yuan clearing banks in offshore markets. It is also expanding its homegrown system that allows global banks to clear and settle cross-border yuan transactions onshore — the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS). The number of direct participants in the CIPS grew to 79 in March. Meanwhile, China has signed or scaled up the size of currency swap pacts with many countries.

In February, the central banks of China and Brazil signed an agreement to set up yuan clearing arrangements in the South American country, with the Brazilian branch of Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Ltd., the world’s largest lender by assets, authorized to be the clearing bank.

Just one month later, a Brazilian bank controlled by China’s Bank of Communications Co. Ltd. became South America’s first direct participant in the CIPS.

Such efforts may encourage small and midsize Brazilian trade companies to use the yuan more, but do little to help the redback win the favor of large businesses given the U.S. dollar’s unrivalled dominance in global trade, Alessandro Golombiewski Teixeira, an economic adviser to former Brazilian President Dilma Vana Rousseff, told Caixin.

The yuan is still far from being a key global currency. It might be picking up momentum, but it’s yet early days, scholars said.

While the yuan won’t supplant the U.S. dollar any time soon, the Chinese currency has the potential to shake the status quo by leaping over the British pound and Japanese yen to become the third-most-popular currency in the world, said a person working at a Russian branch of a major Chinese bank.

But the beyond the popularity ranking, the growing international use of the yuan matters because it heralds a world in which countries will no longer have to depend exclusively on the dollar, or the U.S.-controlled financial system that underpins it. That has long been a goal of Chinese policymakers.

A multipolar international monetary system is emerging as the greenback loses some of its absolute advantages, Peng Wensheng, chief economist at China International Capital Corp. Ltd., wrote in a research report in June.

Growing traction

As the yuan gradually becomes a go-to currency for settling international trade and investment, it is driving greater demand for the redback in offshore markets.

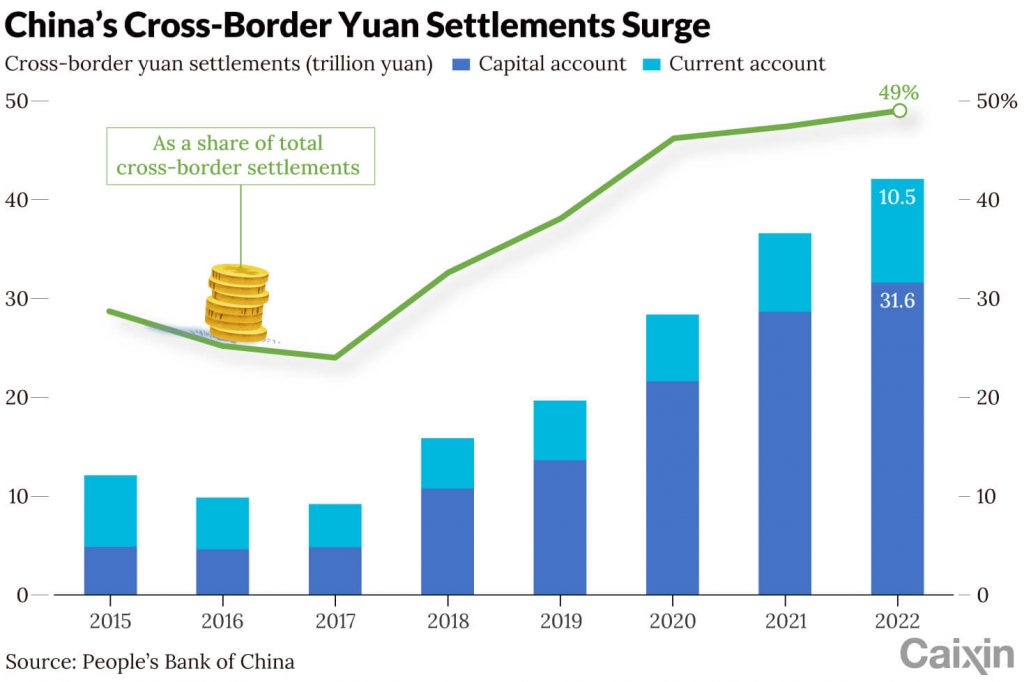

Last year, 49%, or 42.1 trillion yuan ($6.1 trillion), of China’s cross-border settlements used the yuan, according to a February report released by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). Of these yuan settlements, 10.5 trillion yuan occurred under the current account, which chiefly included trade in goods and services.

Meanwhile, with its rising purchasing power and growing imports of bulk commodities, the world’s second-largest economy has been aggressively pushing for yuan-based pricing in commodities in recent years.

“The logic is quite similar to that of petrodollars,” said Shao Yu, chief economist at Orient Securities Co. Ltd., referring to a 1970s system in which the dollar became the currency of choice for international oil trade. “The yuan aims to be pegged to ‘a basket of’ commodities, which is not limited to oil.”

In 2021, China logged 405.5 billion yuan in yuan-settled cross-border trade in major commodities such as crude oil, iron ore, copper, and soybeans, a year-on-year increase of 42.8%, according to the 2022 RMB internationalization report published by the PBOC last September. China has not yet released relevant data for last year.

As recently as March, China chalked up another milestone in the yuan’s use in global energy trade, when state-owned China National Offshore Oil Corp. completed the country’s first yuan-settled import of liquefied natural gas from France’s TotalEnergies.

But it is difficult for yuan’s internationalization to make breakthroughs if it’s only based on trade between China and other countries, according to Zhang Liqing, director of the center for international finance studies at the Central University of Finance and Economics.

The internationalization of the yuan won’t graduate to the next level until it is widely used as a third-party currency in global trade, Zhang said. That’s when actors from two countries other than China use the yuan to settle trade transactions, much like many currently do with dollars.

Meanwhile, the further opening of China’s capital markets is boosting the global popularity of the yuan for investment, with the currency growing more attractive for overseas companies to raise money in.

Last year, China’s cross-border yuan settlements under the capital account hit 31.6 trillion yuan, up 10% from 2021 and accounting for 75% of the total, the PBOC’s February report shows.

In Hong Kong, the world’s largest offshore yuan hub, the issuance of yuan-denominated bonds — known as dim sum bonds — jumped 31% year-on-year to a record high of 143.4 billion yuan in 2022, according to data from the Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

The currency is also gaining traction in other offshore markets, most notably in Russia, which has been trying to bypass Western sanctions that aimed at cutting it off from the dollar-dominated global financial system after it invaded Ukraine in February 2022.

Yuan-denominated bonds boomed in Moscow last year, with a number of Russian giants, including aluminum producer United Co. Rusal International PJSC and gold producer Polyus PJSC, offering large-scale yuan-denominated bonds to lure investors.

Such bond sales quickly reached more than 40 billion yuan over a couple of months, according to the source at a Russian branch of a major Chinese bank.

The yuan has also gained share among the world’s currency reserves, ranking fifth behind the U.S. dollar, the euro, the Japanese yen and the British pound, according to data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

About 2.69% of official foreign exchange reserves worldwide were denominated in the yuan at the end of 2022, IMF data show. That’s up from just over 1% in 2016, when the Chinese currency was first included in the special drawing rights currency basket.

As central banks, especially those of developing countries including oil producers in the Middle East, look to diversify their holdings, the yuan is a “relatively quality and stable choice,” given that there are not many suitable non-Western sovereign currencies to choose from, the person from a major Chinese bank’s Russian branch said.

In the meantime, the CIPS, which has been developing China’s answer to the SWIFT global payments messaging network, had 79 direct participants as of the end of March, up from 75 at the end of 2021. Many of them are overseas branches of major Chinese banks.

The number of indirect participants grew to 1,348 from 1,184 over the same period, with some 75% of the total based in Asia.

However, the system’s size pales in comparison to SWIFT, which boasts more than 11,000 connected institutions.

Heated competition

China’s strict capital controls have long been a drag on the yuan’s internationalization push, making it difficult to erode the dollar’s status as the world’s dominant currency, industry insiders said.

The yuan is the world’s fifth-most-active currency for global payments, according to a monthly tracker of the currency by SWIFT. Its share stood at 2.26% in March, up 0.06 percentage points year-on-year. By comparison, the U.S. dollar’s share of global payments stood at 41.74% in March.

The biggest competitors of the U.S. dollar are the euro and digital currencies, instead of the yuan, said the president of a major Chinese bank’s European branch.

“On the foreign-reserves front, diversification away from the dollar has not meant diversification toward the renminbi, in the main, but rather toward the Korean won, Singapore dollar, Swedish krona, Norwegian krone, and other nontraditional reserve currencies,” said Barry Eichengreen, a professor of economics and political science at the University of California at Berkeley.

The yuan’s internationalization index stood at 2.86 in the first quarter of 2022, up from 2.8 at the end of 2021, but still way behind the U.S. dollar’s reading of 58.13, the euro’s 21.56, the British pound’s 8.87, and the Japanese yen’s 4.96, according to the 2022 RMB internationalization report.

There is no shortcut for any currency to become a global one in the long run, which must be backed by an open capital account, stable and well-functioning financial markets, and a sound rule-of-law system, a person from the Bank for International Settlements told Caixin.

Read also the original story.

caixinglobal.com is the English-language online news portal of Chinese financial and business news media group Caixin. Global Neighbours is authorized to reprint this article.

Image: RHJ – stock.adobe.com